The question: “But I only had one lymph node removed when they did my sentinel node biopsy. How could I possibly develop lymphedema if just one little node is gone?”

The answer: Well, let’s take a quick-and-dirty look at how those nodes are distributed and how they work.

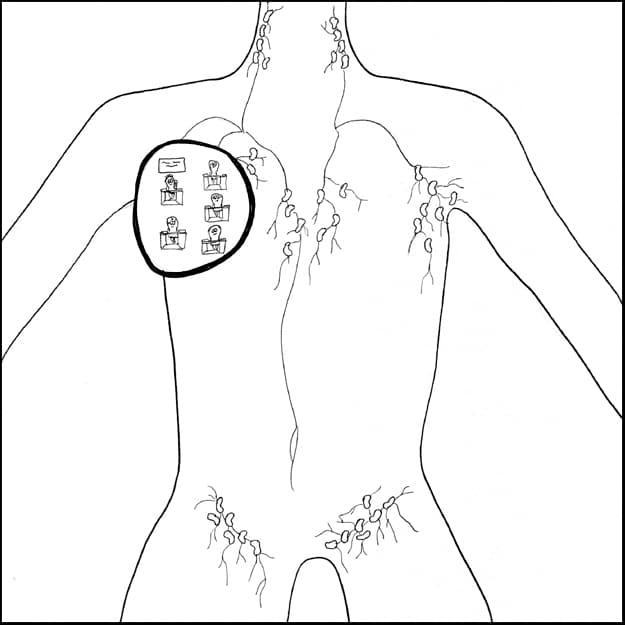

We’ve got lymph nodes spread around our bodies, but there are certain larger groupings of nodes in places like your neck (cervical nodes), your armpits (axillary nodes), and your groin (inguinal nodes). For this example, we’ll focus on the nodes in the axillary region (“axilla” being the proper-albeit-less-humorous name for “armpit”). Think of all these regions as office departments in the corporation that is you.

These little superheroes have multiple tasks – including filtering out harmful stuff like dirt and pathogens, and producing white blood cells called lymphocytes – but for the purposes of this illustration, we’ll talk about their role in fluid balance.

So here in the “right axilla department,” we can see the nodes hard at work. They’re reabsorbing a lot of the water content from the lymphatic fluid, which reduces the amount of lymph that goes back into the venous system.

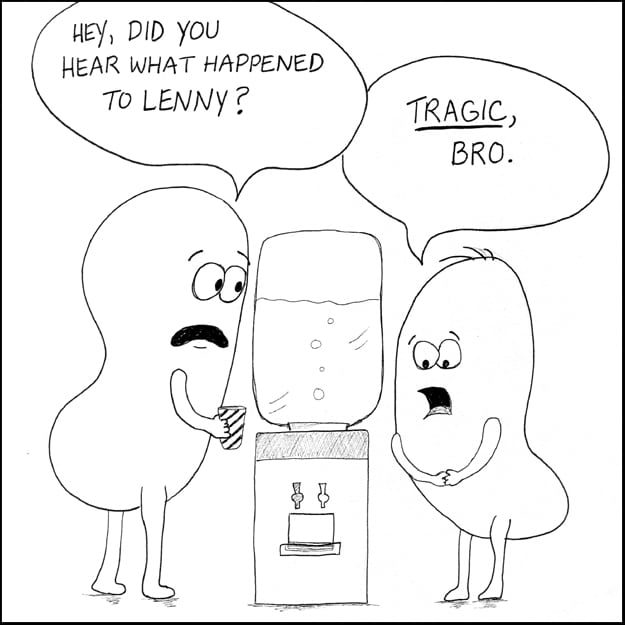

And let’s say just one of these axillary lymph nodes (along with parts of the transport vessels that run to and from that node) gets taken out of the equation because of a sentinel node biopsy or for some other reason. We’ll call that node “Lenny.”

Many times, that department can totally keep on truckin’, the other neighboring nodes can make up for Lenny’s workload, they re-route the fluid through other nearby lymphatic vessels, and they never even miss the guy. This can happen for a while, or even indefinitely.

But other times, that department really feels Lenny’s absence, and the amount of fluid that needs to get processed out of the tissues of that quadrant and get back into the cardiovascular system can get overwhelming.

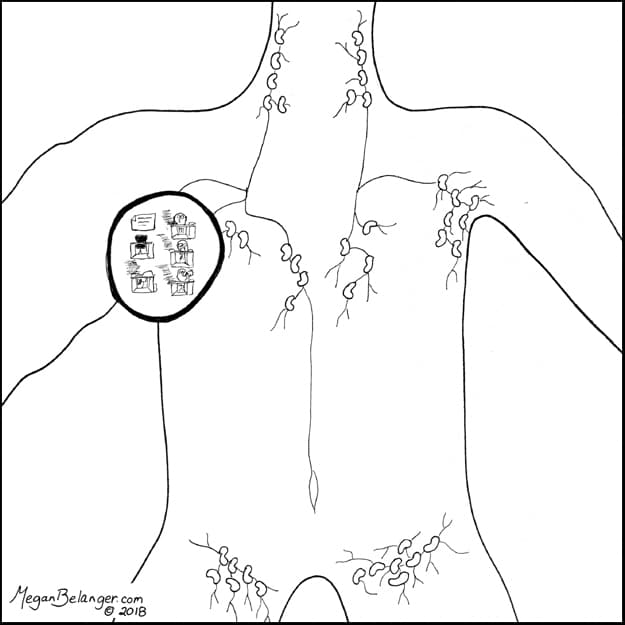

This feeling of being “understaffed” can happen right after a node or nodes are removed, or it can happen as much as years down the road if the lymphatic load increases to a point where the department just can’t handle it as efficiently anymore.

When the lymphatic system gets backed up in a particular region, this can sometimes cause the tissues in that quadrant to swell with protein-rich lymphatic fluid, called lymphedema, and the result can be swelling that you can feel and often see.

So even with only one lymph node removed, the risk for lymphedema still technically exists, though it’s thought to be less compared to multiple lymph nodes having been taken out (imagine Lenny and six or seven of his co-workers disappearing). The risk is low, but it is real.

And plenty of people will never develop lymphedema at all. The hope is that future research in this field will focus on better predicting which people might develop lymphedema. This would mean targeted prevention and intervention strategies, and individualized plans for risk-reducing behaviors. In the meantime, the National Lymphedema Network has some general “healthy habits” that people who might be at risk for lymphedema can follow to help reduce that chance of developing swelling. Check it out here.

Stay tuned for more episodes of “Under Your Skin” on lymphedema and manual lymphatic drainage! There are many more nerdy stories to tell!